© Pint of Science, 2025. All rights reserved.

My name is Bob Sparham and I am a graphic artist and printmaker, however, I also trained as a historian and I am a Shakespeare scholar. My Creative Reactions project for the Pint of Science 2020 online virtual festival is an attempt to unify my disciplines particularly as I have been interested in the history of Astronomy since hearing an inspiring lecture on Galileo when I was at University. It was produced after very interesting actual and e-mail discussions with my scientist Ulrike Kuchner from the University of Nottingham Centre for Astronomy and particle theory (although of course any mistakes or errors are entirely my own) for the project which is based on my astronomical observation with my telescope from my back garden.

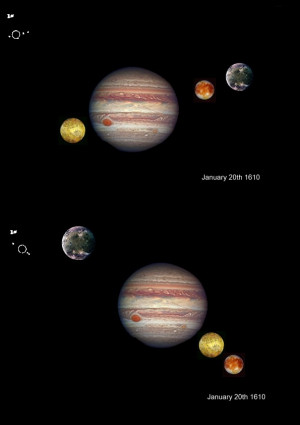

For three summer nights in January ten years ago, I observed Jupiter and I was surprised by the speed that the four Satellites, the four Galilean moons orbited the planet. It was a beautiful sight and one which has stayed with me in the years since, indeed my telescope is roughly the same size as the one which Galileo used to make his important observations in January 1610. The four main characters in our story were Galileo who worked through the nights of 7th-24th January making his observations and sketching the results, William Shakespeare who was in London either planning or writing his last solo play The Tempest, the astronomer Johannes Kepler who was in Prague working on his Rudolphine Tables and a comprehensive set of specific predictions of planet and star positions based upon the observations of the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe.

However the author of the question above which is at the heart of this project, the playwright Christopher Marlow was in his grave, an unmarked grave in the churchyard of St. Nicholas, Deptford (indeed I personally wonder if Faustus’s question above might have been the cause of his murder?)

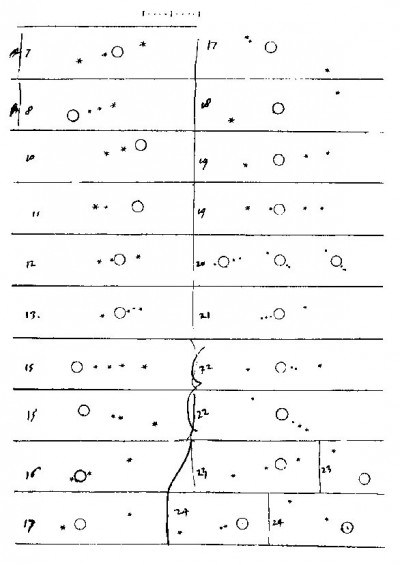

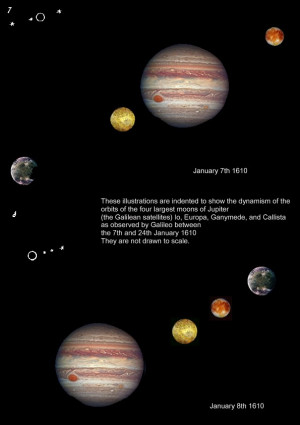

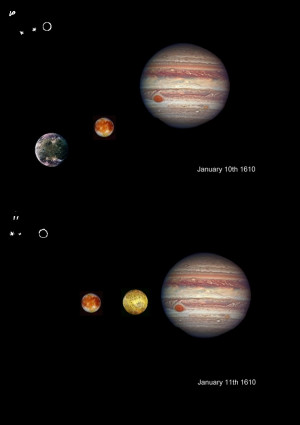

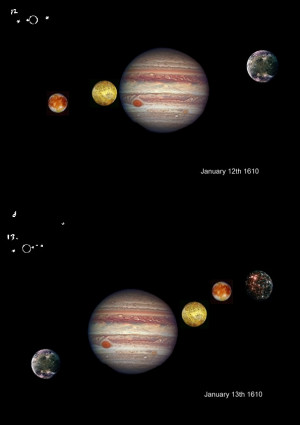

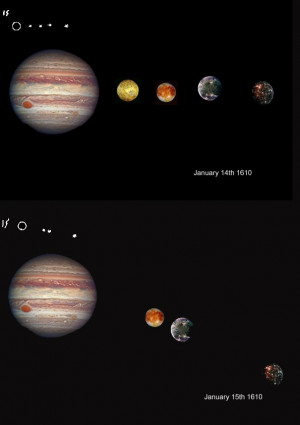

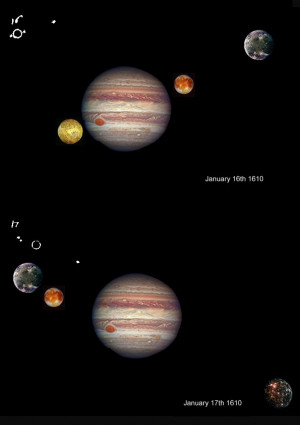

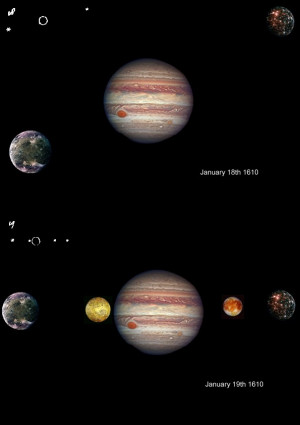

I believe that the publication of Galileo’s observations was nothing less than the most important event of the Early Modern period in political and cultural terms as much as in Astronomical. Therefore for the visual part of the project I have decided to illustrate Galileo’s sketches of the 7th-24th January 1610 with a series of montages of Jupiter and the Galilean moons. I hope both that these montages will make the speed of the moon’s orbits clearer to the lay reader and I also hope that I can make the meaning of them, in a 17th century context, clearer to lay readers in this text. I shall argue that these events, these observations can best be understood in terms of a tension between Falsification, and the Lovejoy Paradigm. Let us define our terms:-

Falsification, is a scientific model Falsification principle originates from Karl Popper's philosophy of science: 'Statements are scientific if our empirical experiences could potentially falsify them' this distinguishes science from non-science 'Any theory that is impossible to disprove is no valid theory at all.' - Karl Popper

The Lovejoy Paradigm however is my name for one of my intellectual hero Arthur Lovejoy’s key points that he wrote in his book the Great Chain of Being:-

There are, first, implicit or incompletely explicit assumptions, or more or less unconscious mental habits, operating in the thought of an individual or a generation. It is the beliefs which are so much a matter of course that they are rather tacitly presupposed than formally expressed and argued for, the ways of thinking which seem so natural and inevitable that they are not scrutinized with the eye of logical self-consciousness, that often are most decisive of the character of a philosopher’s doctrine, and still oftener of the dominant intellectual tendencies of an age.

A.O. Lovejoy The Great Chain of Being.

Introduction: The Study of the History of Ideas.1936

The greatest of our implicit or incompletely explicit assumptions, or more or less unconscious mental habits, are about history that it is a process going from somewhere to somewhere. A process with a beginning, a middle and an end, a process similar to Darwinian evolution and a process which moreover advances in incremental steps. These steps are usually taken by a genius whose work revolutionised previous thinking and takes their subject forward. In our study Galileo and Kepler are often seen as people who take that role as geniuses who helped create a new astronomy. However I shall argue that the reality is more complex than that. The history of Western Astronomy should be seen not as a linear process of an escape from darkness towards enlightenment as we almost always view our history, but rather as a process where very bad Ancient Greek ideas about the cosmos were gradually replaced by very good slightly younger Ancient Greek ideas about the cosmos from a different school of Greek thought, from what might be termed the school of Archimedes, rather than the school of Plato and Aristotle refighting a battle that had first been fought in the 2nd century BC but this time with a different result. For example, why did Copernicus put forward the heliocentric model of the Cosmos? Because he had read an account of the heliocentric ideas of Aristarchus of Samos and this model seemed to him to be more aesthetically pleasing than Ptolemy’s Platonic and Aristotelian epicycles of complexity upon complexity. Another example of The Lovejoy Paradigm I feel lies in our inability to try to understand historical cultures in their own terms rather than reflecting back our culture onto them. An example of this tendency can, I believe, be seen in the amusing, but misleading comedy in the TV series Upstart Crow where the whole of the comedy rests upon finding elements of our culture in an Elizabethan situation. This I feel illustrates our unconscious mental habit of not understanding the cultural nature of our own concerns and thinking of them as in some way universal, as in Will Shakespeare’s endless difficulties with the public transport system between London and Stratford on Avon. So if we think of the relationship between Astronomy and the popular culture of the early modern period, we tend to imagine it as being similar to our own relationship between Astronomy and our popular culture, interesting things, such as the discovery two years ago of Oumuamua (the first object outside the Solar System), are taken up briefly then fade out of public consciousness.

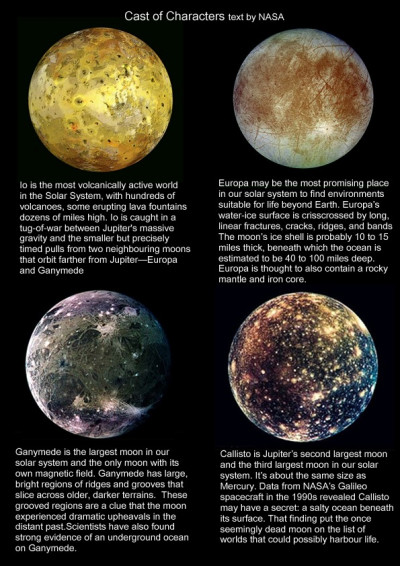

Sketches of the four moons of Jupiter, as seen by Galileo through his telescope. What he saw are the four larger moons of Jupiter, Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. The drawing depicts observations from the time period January 7th to 24th 1610. Galileo had considerable difficulty in recognizing the true meaning of what he was seeing; Callisto often lay outside the (restricted) field of view of his telescope, Io was often lost in Jupiter's glare, and some moon occasionally disappeared in Jupiter's shadow or behind or in front of the planet itself. As above my montages are indented to give a lay reader a clearer picture of what they meant in a 17th century context; they are the visual element of my Creative Reactions.

|

|

|

|

Astronomy in the Early Modern period was very different from today. It was the Queen of sciences and its theories (though they were not called theories at the time) were at the very centre of public debate and the most important justification for the existing social and political arrangements of the state. For example, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, Protestant leader of the Reformation wrote a sermon called the Homily of Obedience in 1547 after the accession of Edward VI. In it, he wrote that obeying the King equated to obeying God, something that was particularly important as Edward VI did not command the same level of respect as Henry, in most part because he was only nine years old when he became King. The book’s publication came with a royal injunction (from Edward VI) mandating the homily’s continual use, in perpetuity, throughout all churches in England. As everybody in England had by law to attend church every Sunday, the content of the liturgy put before the people in every church four times a year was of major political importance. Read now a section from the Homily:- Thomas Cranmer HOMILY ON OBEDIENCE from “Book of Homilies” (1547)-

Almighty God hath created and appointed all things in heaven, earth, and waters, in a most excellent and perfect order. In Heaven, he hath appointed distinct and several orders and states of Archangels and Angels. In earth he hath assigned and appointed Kings, Princes, with other governors under them, in all good and necessary order. The water above is kept, and raineth down in the proper time and season. The Sun, Moon, Stars, Rainbow, Thunder, Lightning, Clouds, and all Birds of the air, do keep their order. The Earth, Trees, Seeds, Plants, Herbs, Corn, Grass, and all manner of Beasts keep themselves in order: all the parts of the whole year, as Winter, Summer, Months, Nights and Days, continue in their order: all kinds of Fishes in the Sea, Rivers, and Waters, with all Fountains, Springs, yea, the Seas themselves keep their comely course and order: and man himself also hath all his parts both within and without, as soul, heart, mind, memory, understanding, reason, speech, with all and singular corporal members of his body in a profitable, necessary, and pleasant order: every degree of people in their vocation, calling and office, hath appointed to them their duty and order: some are in high degree, some in low, some Kings and Princes, some inferiors and subjects, Priests, and lay men, masters and servants, fathers, and children, husbands and wives, rich and poor, and everyone have need of other, so that in all things is to be lauded and praised the goodly order of God, without the which no house, no City, no Commonwealth can continue and endure, or last. For where there is no right order, there reigneth all abuse, carnal liberty, enormity, sin, and Babylonicall confusion. Take away Kings Princes, Rulers, Magistrates, Judges, and such estates of God’s order, no man shall ride or go by the highway unrobbed, no man shall sleep in his own house or bed unkilled, no man shall keep his wife, children, and possession in quietness, all things shall be common, and there must needs follow all mischief, and utter destruction both of souls, bodies, goods, and commonwealths. Therefore, let us subjects do [the duties to which we are bound], giving hearty thanks to God, and praying for the preservation of this godly order. Let us all obey even from the bottom of our hearts, all their godly proceedings, laws, statutes, proclamations, and injunctions, with all other godly orders. Let us consider the Scriptures of the holy Ghost, which persuade and command us all obediently to be subject, first and chiefly to the Kings Majesty, supreme governor over all, and the next to his honourable counsel, and to all other noble men, Magistrates, and officers, which by God’s goodness, be placed and ordered.

|

|

|

|

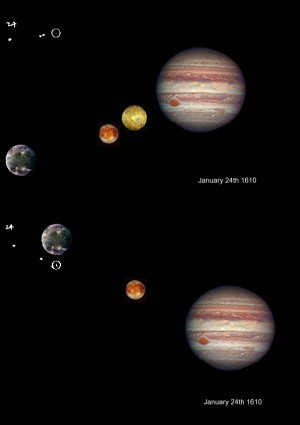

Early Modern English thinkers such as Shakespeare (far from worrying about the deficiencies of public transport!) believed that God had established the Divine Order and that God wanted it to be followed and he would punish humanity if it were not. Known as The Great Chain of Being, the shape and the form of the Universe was not as we have seen, matter for purely academic debate; rather it was a matter of critical importance to each and every individual and each part of Society. As it says in the BBC’s Bitesize Revision Notes Page 2:-

Elizabethans believed that God set out an order for everything in the universe. This was known as the Great Chain of Being. On Earth, God created a social order for everybody and chose where you belonged. In other words, the king or queen was in charge because God put them there and they were only answerable to God (the Divine Right of Kings). This meant that disobeying the monarch was a sin, which was handy for keeping people in their place! It also led to the idea that if the wrong person was monarch everything would go wrong for a country, including whether the crops would be good, or if animals behaved as they should.

The Elizabethans were very superstitious. The Great Chain of Being includes everything from God and the angels at the top, to humans, to animals, to plants, to rocks and minerals at the bottom. It moves from beings of pure spirit at the top of the Chain to things made entirely of matter at the bottom. Humans are pretty much in the middle, being mostly mortal, or made of matter, but with a soul made of spirit. The theory started with the Greek philosophers Aristotle and Plato, but was a basic assumption of life in Elizabethan England. You were a noble, or a farmer, or a beggar, because that was the place God had ordained for you. The Great Chain of Being is a major influence on Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Macbeth disturbs the natural order of things by murdering the king and stealing the throne. This throws all of nature into uproar, including a story related by an old man that the horses in their stables went mad and ate each other, a symbol of unnatural happenings.

Indeed The Great Chain of Being was one of Shakespeare main themes, appearing in plays such as Troilus and Cressida, Julius Caesar as well as in Macbeth. Each and every person, it argues had a duty to act in harmony with the system, as it says in the Homily:-

…every degree of people in their vocation, calling and office, hath appointed to them their duty and order: some are in high degree, some in low, some Kings and Princes, some inferiors and subjects, Priests, and lay men, masters and servants, fathers, and children, husbands and wives, rich and poor, and everyone have need of other, so that in all things is to be lauded and praised the goodly order of God, If someone or something were to break the Divine Order by not being obedient to whatever or whoever was above, them if the person or society went against the God's will, Gods plan of the Great Chain of Being, they would be punished by cosmic disharmony.

The Great Chain of Being: From Didacus Valades, Rhetorica Christiana 1579

Troilus and Cressida | Act 1, Scene 3

The heavens themselves, the planets and this centre

Observe degree, priority and place,

Insisture, course, proportion, season, form,

Office and custom, in all line of order;

And therefore is the glorious planet Sol

In noble eminence enthroned and sphered

Amidst the other; whose medicinable eye

Corrects the ill aspects of planets evil, 545

And posts, like the commandment of a king,

Sans cheque to good and bad: but when the planets

In evil mixture to disorder wander,

What plagues and what portents! what mutiny!

What raging of the sea! shaking of earth! 550

Commotion in the winds! frights, changes, horrors,

Divert and crack, rend and deracinate

The unity and married calm of states

Quite from their fixure! O, when degree is shaked,

Which is the ladder to all high designs,

Which is the ladder to all high designs,

Then enterprise is sick! How could communities,

Degrees in schools and brotherhoods in cities,

Peaceful commerce from dividable shores,

The primogenitive and due of birth,

Prerogative of age, crowns, sceptres, laurels,

But by degree, stand in authentic place?

Take but degree away, untune that string,

And, hark, what discord follows! each thing meets

In mere oppugnancy: the bounded waters

Should lift their bosoms higher than the shores

And make a sop of all this solid globe:

Strength should be lord of imbecility,

And the rude son should strike his father dead:

Force should be right; or rather, right and wrong

Troilus and Cressida 1.3

Macbeth 2.3.

LENNOX

The night has been unruly: where we lay,

Our chimneys were blown down; and, as they say,

Lamentings heard i' the air; strange screams of death,

And prophesying with accents terrible

Of dire combustion and confused events

New hatch'd to the woeful time: the obscure bird

Clamour'd the livelong night: some say, the earth

Was feverous and did shake.

MACBETH

'Twas a rough night.

LENNOX

My young remembrance cannot parallel

A fellow to it.

Re-enter MACDUFF

MACDUFF

O horror, horror, horror! Tongue nor heart

Cannot conceive nor name thee!

MACBETH LENNOX

What's the matter.

MACDUFF

Confusion now hath made his masterpiece!

Most sacrilegious murder hath broke open

The Lord's anointed temple, and stole thence

The life o' the building!

MACBETH

What is 't you say? the life?

LENNOX

Mean you his majesty?

MACDUFF

Approach the chamber, and destroy your sight

With a new Gorgon: do not bid me speak;

See, and then speak yourselves.

Exeunt MACBETH and LENNOX

Awake, awake!

Ring the alarum-bell. Murder and treason!

Banquo and Donalbain! Malcolm! awake!

Shake off this downy sleep, death's counterfeit,

And look on death itself! up, up, and see

The great doom's image! Malcolm! Banquo!

As from your graves rise up, and walk like sprites,

To countenance this horror! Ring the bell.

Macbeth 2.3.

Julius Caesar 1.3

SCENE III. The same. A street.

Thunder and lightning. Enter from opposite sides, CASCA, with his sword drawn, and CICERO

CICERO

Good even, Casca: brought you Caesar home?

Why are you breathless? and why stare you so?

CASCA

Are not you moved, when all the sway of earth

Shakes like a thing unfirm? O Cicero,

I have seen tempests, when the scolding winds

Have rived the knotty oaks, and I have seen

The ambitious ocean swell and rage and foam,

To be exalted with the threatening clouds:

But never till to-night, never till now,

Did I go through a tempest dropping fire.

Either there is a civil strife in heaven,

Or else the world, too saucy with the gods,

Incenses them to send destruction.

CICERO

Why, saw you any thing more wonderful?

CASCA

A common slave--you know him well by sight--

Held up his left hand, which did flame and burn

Like twenty torches join'd, and yet his hand,

Not sensible of fire, remain'd unscorch'd.

Besides--I ha' not since put up my sword--

Against the Capitol I met a lion,

Who glared upon me, and went surly by,

Without annoying me: and there were drawn

Upon a heap a hundred ghastly women,

Transformed with their fear; who swore they saw

Men all in fire walk up and down the streets.

And yesterday the bird of night did sit

Even at noon-day upon the market-place,

Hooting and shrieking. When these prodigies

Do so conjointly meet, let not men say

'These are their reasons; they are natural;'

For, I believe, they are portentous things

Unto the climate that they point upon.

CICERO

Indeed, it is a strange-disposed time:

But men may construe things after their fashion,

Clean from the purpose of the things themselves.

Come Caesar to the Capitol to-morrow?

CASCA

He doth; for he did bid Antonius

Send word to you he would be there to-morrow.

CICERO

Good night then, Casca: this disturbed sky

Is not to walk in.

CASCA

Farewell, Cicero.

The central political problem for the Elite in the Early Modern Period (and indeed throughout the Medieval period as well) was to justify their Hegemonic status in a very religious society, one in which Christ himself had preached against social distinctions. The Elite argument was roughly ‘The reason that our small group of myself, my family and friends have lots of money and power, whilst you peasants, you far bigger group, including your family and friends have no money and no power is not because we are sinners selfishly ignoring Christ’s teaching for our own ends. No, it is because social distinctions are natural, provable, demonstrable features of the Structure of the Universe.’ That is the message of The Homily on Obedience, a message which Shakespeare reinforced with his descriptions of the cosmic disharmony which would result from breaches of the ‘natural order’ established by the Great Chain. It was a profoundly conservative message designed above all to defend hegemony and if, in defence of that hegemony, scientific principles were breached then so be it. Read what Isaac Newton said about Ptolemy in the context of a text explaining his work from the University of Saint Andrews:-

“The Almagest is the earliest of Ptolemy's works and gives in detail the mathematical theory of the motions of the Sun, Moon, and planets. Ptolemy made his most original contribution by presenting details for the motions of each of the planets. The Almagest was not superseded until a century after Copernicus presented his heliocentric theory in the De revolutionibus of 1543. Grasshoff writes :-

Ptolemy's "Almagest" shares with Euclid's "Elements" the glory of being the scientific text longest in use. From its conception in the second century up to the late Renaissance, this work determined astronomy as a science. During this time the "Almagest" was not only a work on astronomy; the subject was defined as what is described in the "Almagest

We shall try to note down everything which we think we have discovered up to the present time; we shall do this as concisely as possible and in a manner which can be followed by those who have already made some progress in the field. For the sake of completeness in our treatment we shall set out everything useful for the theory of the heavens in the proper order, but to avoid undue length we shall merely recount what has been adequately established by the ancients. However, those topics which have not been dealt with by our predecessors at all, or not as usefully as they might have been, will be discussed at length to the best of our ability.

Ptolemy first of all justifies his description of the universe based on the earth-centred system described by Aristotle. It is a view of the world based on a fixed earth around which the sphere of the fixed stars rotates every day, this carrying with it the spheres of the sun, moon, and planets. Ptolemy used geometric models to predict the positions of the sun, moon, and planets, using combinations of circular motion known as epicycles. Having set up this model, Ptolemy then goes on to describe the mathematics which he needs in the rest of the work. In particular he introduces trigonometrical methods based on the chord function.

Mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk

Isaac Newton [Ptolemy] developed certain astronomical theories and discovered that they were not consistent with observation. Instead of abandoning the theories, he deliberately fabricated observations from the theories so that he could claim that the observations prove the validity of his theories. In every scientific or scholarly setting known, this practice is called fraud, and it is a crime against science and scholarship.

Perhaps the social importance of The Great Chain hypothesis explains why its defenders fought so bitterly to defend it, witness showing Galileo the instruments of torture and putting him under house arrest. However there was one Elizabethan playwright whose attitude to the Great Chain was more subtle and nuanced than Shakespeare’s resolute defence of orthodoxy.

John Case’s 1588 Frontispiece of his book Sphaera Civitates, illustrates the Queen’s position; the image of the Great Chain makes explicit the links between the heavenly and earthly systems of order. Note how each sphere represents a particular aspect of Elizabeth’s rule, thus each of the seven planetary spheres represents one of the queen’s virtues, Saturn = majesty, Jupiter = prudence, Mars = strength (of mind), Sun= piety, Venus = mercy, Mercury = eloquence, and the Moon = prosperity . This idea is related to Plato’s concept that the spheres nearest to God on the outside of the circle were more perfect than those nearer the centre, nearer to the imperfect messy Earth.

The playwright who challenged the Elizabethan order was Christopher Marlowe in his play The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus. In the play, a demon (a representative of the devil himself) named Mephistophilis is a messenger. Faustus strikes a deal with Lucifer: he is to be allotted 24 years of life on Earth, during which time he will have Mephistophilis as his personal servant and the ability to use magic; however, at the end he will give his body and soul over to Lucifer as payment and spend the rest of time as one damned to Hell. This deal is to be sealed in the form of a contract written in Faustus' own blood. After signing the pact Faustus begins by asking Mephistophilis a series of Astronomy related questions. However, the demon seems to be quite evasive and finishes with a Latin phrase, Per inoequalem motum respect totes ("through unequal motion with respect to the whole thing"). Here is how Marlowe’s text reads:-

FAUSTUS Come, Mephistophilis, let us dispute again,

And argue of divine astrology. 35

Tell me, are there many heavens above the moon

Are all celestial bodies but one globe,

As is the substance of this centric earth?

MEPHIST. As are the elements, such are the spheres,

Mutually folded in each other's orb, 40

And, Faustus, All jointly move upon one axletree,

Whose terminine is term'd the world's wide pole;

Nor are the names of Saturn, Mars, or Jupiter

Feign'd, but are erring stars.

FAUSTUS. But, tell me, have they all one motion, both situ et 45

tempore?

MEPHIST. All jointly move from east to west in twenty-four hours

upon the poles of the world; but differ in their motion upon

the poles of the zodiac.

FAUSTUS. Tush,

These slender trifles Wagner can decide: 50

Hath Mephistophilis no greater skill?

Who knows not the double motion of the planets?

The first is finish'd in a natural day;

The second thus; as Saturn in thirty years;

Jupiter in twelve; Mars in four; the Sun, Venus, and 55

Mercury in a year; the Moon in twenty-eight days.

Tush, these are freshmen' suppositions.

But, tell me, hath every sphere a dominion or intelligentia ?

MEPHIST. Ay.

FAUSTUS. How many heavens or spheres are there? 60

MEPHIST. Nine; the seven planets, the firmament, and the empyreal

heaven.

FAUSTUS. Well, resolve me in this question; why have we not

conjunctions, oppositions, aspects, eclipses, all at one time,

but in some years we have more, in some less? 65

MEPHIST. Per inoequalem motum respectu totius inœqualis (through unequal motion with respect to the whole thing)

If we look at the Astronomical questions in Dr Faustus in the context of the illustration above from the Fludd map the Great Chain

F Tell me, are there many heavens above the moon, Are all celestial bodies but one globe, As is the substance of this centric earth? M As are the elements, such are the spheres,

Mutually folded in each other's orb, And, Faustus, All jointly move upon one axletree, Whose terminine is term'd the world's wide pole

Following Aristotelian science matter in the world was believed to be made up from a combination of four elements, Earth, Water, Air and Fire. Both Earth and Water clearly had an earthly existence so Air and Fire had spheres allocated to them. As you move outwards each sphere encloses the next, from the sphere of the Moon to the outermost sphere of Saturn and they all turn on the same axis, the end terminine of which is called the pole.

Nor are the names of Saturn, Mars, or Jupiter Feign'd, but are erring stars. F But, tell me, have they all one motion, both situ et tempore? (in space and time)M All jointly move from east to west in twenty-four hours upon the poles of the world; but differ in their motion upon the poles of the zodiac. F Who knows not the double motion of the planets? The first is finish'd in a natural day; the second thus; as Saturn in thirty years; Jupiter in twelve; Mars in four; the Sun, Venus, and Mercury in a year; the Moon in twenty-eight days. Tush, these are freshmen 'suppositions.

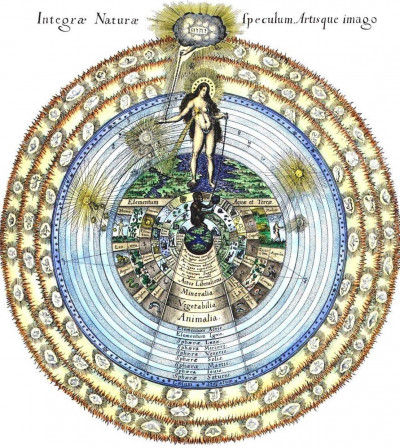

In Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy the circle had a quasi religious status as a perfect form, thus it was very important for the orbits of the planets to be circular as indeed it was functionally. This universe rotated around the earth like a huge wheel rotating around its earthly axle. However there was a major problem for proponents of the Great Chain Theory which Marlowe highlights with the lines:- Nor are the names of Saturn, Mars, or Jupiter Feign'd, but are erring stars and indeed with his:- Who knows not the double motion of the planets? because the motion of the planets (the wanderers in Greek) the erring stars did not seen to be circular. If you observed their motion night on night you could see that they erred by making a double motion a retrograde kind of loop the loop as can be seen in the illustration below.

The Astronomer Ptolemy ‘solved’ this problem around 100AD by arguing that planets rotated around their orbits in circular movements called epicycles. Ptolemy insisted that the job of the astronomer was to explain the motions of the wanderers using only uniform circular motion - the kind of motion that most gears and wheels show, to Save the Appearances as it was known. To make the planets appear to speed up and slow down, three tricks were used. Firstly the epicycles and then secondly to move the observer out of the centre of the circle, putting us into an "eccentric" position. The third trick was called the equant as is shown below. It is noticeable that epicycles, eccentrics and equants are absent from our main 1617 illustration even though it was drawn approximately 1400 years after Ptolemy’s lifetime. Isaac Newton was later to bitterly criticize Ptolemy for changing his observations to fit his theories rather than his theories to fit his observations (see above).

Ptolemy’s Geocentric model to account for the double motion of the planets Diagram of the geocentric trajectory of Mars through several periods of apparent retrograde motion (Astronomia nova, Chapter 1, 1609)

To look at the remaining sections of Marlowe’s text:-

F.But, tell me, hath every sphere a dominion or intelligentia? M. Ay .F How many heavens or spheres are there? M Nine; the seven planets, the firmament, and the empyreal heaven.

A dominion or intelligentia is a controlling power or angel. There were indeed nine spheres on the Fludd map, the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn, in addition the firmament, the realm, sphere of the fixed stars and the empyreal heaven the sphere of pure fire or highest heaven.

It seems to me that these questions, particularly Faustus’ “Well, resolve me in this question; why have we not conjunctions, oppositions, aspects, eclipses, all at one time, but in some years we have more, in some less? are empirical questions in the scientific falsification tradition 'Statements are scientific if our empirical experiences could potentially falsify them’ Faustus is interrogating the Great Chain hypothesis. He was asking questions that Kepler and Galileo were to resolve in the next few years. Indeed he seems to have been a Copernican in the revived Greek scientific tradition, Marlowe’ thinking seems to be very far from Shakespeare’s don’t rock, the boat, don’t scare the horses position expressed in:-

Troilus and Cressida 1.3

The heavens themselves, the planets and this centre

Observe degree, priority and place,

Insisture, course, proportion, season, form,

Office and custom, in all line of order;

And therefore is the glorious planet Sol

In noble eminence enthroned and sphered

Amidst the other; whose medicinable eye

Corrects the ill aspects of planets evil,

And posts, like the commandment of a king,

Sans cheque to good and bad: but when the planets

In evil mixture to disorder wander,

What plagues and what portents! what mutiny!

What raging of the sea! shaking of earth!

Commotion in the winds! frights, changes, horrors,

Divert and crack, rend and deracinate

The unity and married calm of states

Quite from their fixure! O, when degree is,

Which is the ladder to all high designs,

Degree was indeed about to be shaken, like it had never been shaken before. The reaction against that shaking by the establishment was fierce in the case of Galileo and I wonder if it might not have been equally fierce in the case of Marlowe?

Kepler and Galileo

My scientist Uli suggested I read a blog about Kepler called Brain Pickings by Maria Popover which indeed I enjoyed very much. However she talks about Kepler as revolutionary; discovering new ideas to take astronomy forward, a position which seems to me to lack a dimension and that dimension was Ancient Greek astronomy. So from my perspective Kepler was a revolutionary rediscovering old ideas to take astronomy forward. So that this probably the most important period in the history of Western Astronomy should be seen not as a linear process of an escape from darkness towards enlightenment as we almost always view our history, but rather as a process where very bad old ideas about the cosmos were gradually replaced by very good old ideas about the cosmos refighting a battle that had first been fought in the 2nd century BC but this time with a different result.

For example, why did Copernicus put forward the heliocentric model of the Cosmos? Because he had read an account of the heliocentric ideas of Aristarchus of Samos and this model seemed to him to be more aesthetically pleasing than Ptolemy’s epicycles of complexity upon complexity. As far as Kepler’s epiphany, his great discovery, that too had ancient Greek origins, to quote from that august and learned journal Wikipedia:-

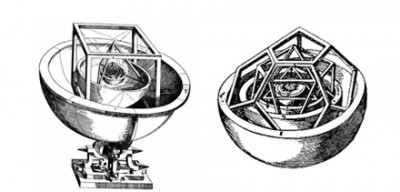

Kepler began experimenting with 3-dimensional polyhedra. He found that each of the five Geometric forms the Platonic solids could be inscribed and circumscribed by spherical orbs; nesting these solids, each encased in a sphere, within one another would produce six layers, corresponding to the six known planets—Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. By ordering the solids selectively—octahedron, icosahedron, dodecahedron, tetrahedron, cube—Kepler found that the spheres could be placed at intervals corresponding to the relative sizes of each planet's path, assuming the planets circle the Sun.

Kepler’s great heliocentric model of the cosmos, with the Platonic Solids the octahedron, icosahedron, dodecahedron, tetrahedron, and the cube ordered inside each other

The traditional Platonic/Aristotelian model of The Great Chain of Being, the seven perfectly circular spheres from Lunae to Saturni (including Solis for the Sun) were made of crystal but the substance of each type of crystal was different. Each was made from the Platonic solids, the octahedron, icosahedron, dodecahedron, tetrahedron, which according to the model gathered together like snowflakes or ice crystals to form each sphere. Thus Kepler’s heliocentric model of the Cosmos is very close to, a linear descendant indeed, of the traditional geocentric Great Chain of Being model of the cosmos.

For me, Kepler’s success came not from the fact that he invented this variation on the Great Chain theme, but rather that he abandoned it when he could not make it fit Tycho Brahe’s empirical evidence of the orbit of Mars. Isaac Newton criticised Ptolemy in that he had developed certain astronomical theories and discovered that they were not consistent with observation. Instead of abandoning the theories, he deliberately fabricated observations from the theories so that he could claim that the observations prove the validity of his theories Kepler’s greatness came from the fact that he refused to follow that path, to Save the Appearances as a Ptolemy type decision was known then. It was that decision which led to his three laws of motion. The second of which was in fact anticipated by the Greeks who built the Antikytheria mechanism their circa 100 BC analogue computer!

To prove his hypothesis of the key role of the Platonic Solids in planetary orbits, Kepler had calculated and recalculated various approximations of Mars' orbit using an equant (the Ptolemaic mathematical tool that Copernicus had eliminated with his system), eventually creating a model that almost agreed with Tycho's observations. But he was not satisfied with the still slightly inaccurate result; at certain points the model differed from the data by up to eight arc minutes. Traditional mathematical methods having failed him, Kepler set about trying to fit an ovoid orbit to the data. Thus by accepting that the model of his great ‘discovery’ did not fit the data accurately enough to be promoted, Kepler became both one of the first modern scientists, and one of the great rebuilders of the Greek scientific tradition.

Based on measurements of the aphelion and perihelion of the Earth and Mars, he created a formula in which a planet's rate of motion is inversely proportional to its distance from the Sun. Verifying this relationship throughout the orbital cycle required very extensive calculation; to simplify this task, by late 1602 Kepler reformulated the proportion in terms of geometry: planets sweep out equal areas in equal times—his second law of planetary motion.

He then set about calculating the entire orbit of Mars, using the geometrical rate law and assuming an egg-shaped orbit. After approximately 40 failed attempts, in late 1604 he at last hit upon the idea of an ellipse, which he had previously assumed to be too simple a solution for earlier astronomers to have overlooked, but as we have seen “From its conception in the second century up to the late Renaissance, this work (the "Almagest")( determined astronomy as a science. During this time the "Almagest" was not only a work on astronomy; the subject was defined as what is described in the "Almagest, Which of course insisted on circular orbits as a matter of faith.

Finding that an elliptical orbit fitted the Mars data, Kepler immediately concluded that all planets move in ellipses, with the Sun at one focus—his first law of planetary motion.

Kepler’s work therefore provided the answer to Faustus’s question “Well, resolve me in this question; why have we not conjunctions, oppositions, aspects, eclipses, all at one time, but in some years we have more, in some less? Conjunctions, oppositions, aspects, eclipses, change from year to year because the positions of planets relative to each other change from year to year as again as Marlowe noted the durations of their orbits are very variable. What an insightful question it was for Marlowe to have asked in the play.

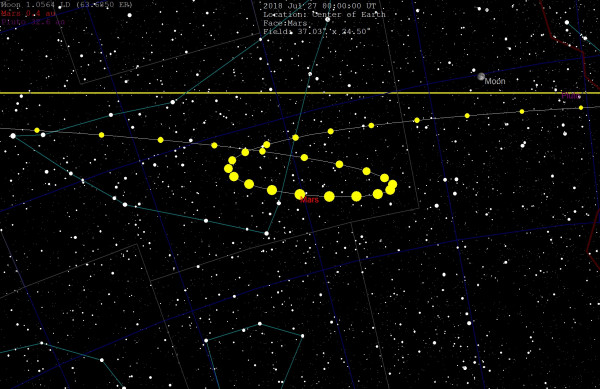

As we have seen, a further major challenge to Platonic/Aristotelian cosmology, came on the 7th January 1610, When Galileo observed with his telescope what he described at the time as "three fixed stars, totally invisible by their smallness". It soon became apparent to him that these objects could not in fact be stars because their movements and the speed of those movements meant that they could not in fact be called fixed anything. On the 10th January, Galileo noted that one of them had disappeared, an observation which he attributed to its being hidden behind Jupiter. Within a few days, he concluded that they were orbiting Jupiter: he had discovered three of Jupiter's four largest moons. He discovered the fourth on the 13th January. Galileo's observations of the satellites of Jupiter: a planet with smaller planets orbiting it did not conform to the principles of Platonic/Aristotelian cosmology, which held that all heavenly bodies should circle the Earth, and many astronomers and philosophers declined to believe that Galileo could have discovered such a thing, refusing even to look through his telescope when he offered them the chance to do so during the later controversy.

Ironically however the Jupiter system, because its large satellites Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto have nearly circular orbits, is the part of the solar system which behaves closest to the Platonic/Aristotelian circular spinning disc model. Its moons move so quickly because they are close to Jupiter and the inner part of a wheel must necessarily move faster than the outer parts.

Notwithstanding that irony, there was, of course, considerable opposition to Galileo’s observations; Galileo's championing of heliocentrism had met with opposition from within the Catholic Church and from some astronomers. The matter was investigated by the Roman Inquisition in 1615, which concluded that heliocentrism was "foolish and absurd in philosophy, and formally heretical since it explicitly contradicts in many places the sense of Holy Scripture".

Hear from Bob and Ulrike to find out more about their collaboration process in our behind-the-scenes post.

About this post

This blog post is part of the Creative Reactions Nottingham 2020 online exhibition. Over the month of September, we will be bringing you different examples of collaborations between art and science, including a chance to get creative yourself. More Creative Reactions Nottingham blog posts.