© Pint of Science, 2025. All rights reserved.

Conspiracy theories are extremely popular; you can find the latest one just by searching “5G coronavirus” on Twitter or Facebook. There are many possible explanations for why some people reject what scientists think in favour of conspiracies, but I want to focus on one in particular. I was scrolling through a Twitter debate on COVID-19 lockdown measures when I noticed a tweet about the Imperial College statistical model, used by the Government to predict the effects of COVID-19. This tweet used the fact that the model was changed as evidence that scientists don’t know what they’re doing. Leaving aside the complicated details of this example, I have noticed that pointing out that scientists make changes is often used to undermine their claims. If scientists keep changing their minds, do they really know what they’re doing?

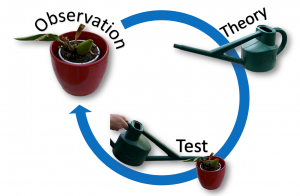

To answer this question, we need to look more closely at what scientists actually do. Scientists spend their time conducting research, looking for answers to the questions posed by the world around us. Research involves observing things around us, suggesting an explanation for what you’ve seen and finally testing that theory with an experiment. Take your houseplant, if you have one, as an example. If you’re not particularly green-fingered, you might notice your plant starts losing its leaves. You spot the soil is dry, wonder if it needs more water and, in order to test your theory, you water it and see if it gets better. If there’s no improvement in the plant, you consider that maybe water is not the problem, but there might be too much sunlight on that windowsill. To test the new hypothesis, you move the plant to a new position and wait to see if anything changes.

The cycle of scientific observations

Most science works like this; a cycle of observations, theories and tests in order to better understand the world around us. Each step of the cycle can be built upon and improved. Scientists are encouraged to comment on each other’s work, and point out flaws or oversights (and some do with slightly more enthusiasm than necessary). To go back to your plant, whilst complaining to your friend about your unsuccessful attempts to stop the loss of leaves, she might point out that this plant always drops its leaves at this time of year. Of course, scientists take a much more informed approach to their research than you might with your houseplant, but the positive impact of having another person offer their suggestions is just as powerful. All new findings are subjected to intense scepticism and scrutiny in the science world both before and during the process of publishing, making the conclusions that come out the other side all the more robust.

The important thing about research is that it is iterative. Every finding that you make is provisional, your ‘best understanding’ of the concept, which only lasts until you learn something more. Scientists rarely make absolute statements. Every result is only ‘true’ until another, even more rigorous experiment is performed and tests the standing theory. In this way, scientists build upon each other’s work.

Of course, scientists are not infallible, and will sometimes make incorrect assumptions or accept things at face value. There are countless examples where scientists have ‘got it wrong’. Before we knew about germs, the scientific consensus on how diseases spread was that people were breathing in ‘bad air’ which made them sick. This theory lasted for centuries and actually hindered the acceptance of new theories, leading to the initial dismissal of evidence collected by John Snow on how cholera seemed to spread through dirty drinking water. The established theory that people got sick from bad air had been around for years, and so must be correct. This just shows how dangerous sticking to the status quo can be for the progress of science.

Scientific understanding of how diseases spread hundreds of years ago was wrong. But thanks to developments in our understanding and technology, we now know many principles we ‘knew’ hundreds of years ago are wrong. We were able to learn about germs partly due to the invention of the microscope. In a similar way, as technology develops, we have access to more tools and techniques that lead to new observations and experiments, all the while improving our understanding of the world around us. In science, changing your mind when you get more data or learn something new is not a bad thing, it is actually fundamental to getting closer to the truth. Science is not just a collection of cold, hard facts. It is an ever-changing view of how the world works.

About the Author

Eva Hamrud is a PhD student at King’s College London. She's currently trying to understand how stem cells work. As well as doing research, she enjoys talking and writing about science, and writes a blog Biology in Context, that aims to give context to different biology topics you might have read about in the news. You can find out more about Eva's writing and the blog via Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.