© Pint of Science, 2025. All rights reserved.

Beermat Doodles artists are a group of Nottingham’s finest illustrators. Typically, they create 5-minute personalised illustrations on blank beermats at live events such as at the Nottingham Craft Beer Festival. Here’s mine from a STEM-On-Notts event we hosted during Nottingham Craft Beer Festival 2019.

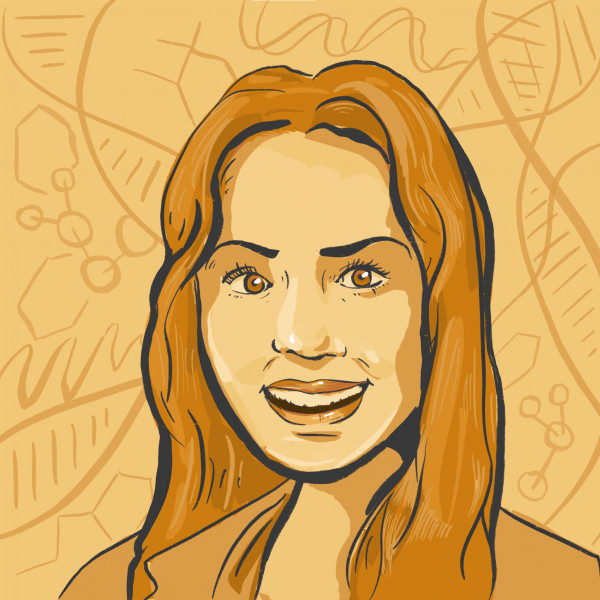

We contacted one of their talented artists, Raphael Achache, who agreed to do some science-inspired portraits of local researchers. However, in the light of a global pandemic, these couldn’t be illustrated live. So we sent Raphael pictures of three researchers along with a summary of their research.

Ben Robinson - PhD student within the Food, Water, Waste Research Group (Faculty of Engineering, University of Nottingham) @escap_aid ([email protected])

Energy and sustainability are like peanut butter and jam, fish and chips or eggs and bacon (for you bacon lovers out there), they are so intrinsically linked that it becomes impossible to talk about one without the other. This is especially true in my focus country Nepal, where 60% of the population don’t have access to clean sources of energy. Thousands die due to the smoke produced from burning firewood to cook, heat themselves, purify water, preserve food and satisfy their socio-cultural tradition of sitting around the fire and passing on the stories of a different generation. The fundamental issue is this; wood is free, other more sustainably produced and managed sources of energy are not.

Whilst this seems simple, in fact, it’s not. The complex relationship between individuals, community, state, government and in some cases international donors are balanced against the complex socio-cultural, economic and environmental contextual needs of rural Nepali households. Even with a fairly robust Government Policy framework around renewable energy access and subsidies, individuals like cooking on an open fire and in the case of a major disaster, like the 2015 earthquake, there is no other option. For rural Nepali individuals the use, or ‘stacking’, of multiple technologies is common. Firewood for rice, gas for curry, a bigger fire outside to cook for the cows, a kerosene cooker for when gas is too expensive, a biodigester outside for cooking in the summer, a small portable rocket stove which can be moved around – the specific use of each technology is tailored to the convenience of using it. Now, what is the most sustainable way forward?

My research doesn’t try to answer this question directly but equip the development practitioners, local government and on-the-ground research organisations to better understand the complex socio-cultural, environmental and financial contextual factors that have become barriers to poverty alleviating technologies. These barriers emerge from fundamental differences in priorities between the technology users (in this case rural Nepali households) and the technology implementers. I have developed a framework and accompanying methodology that brings together these different priorities, linking the need of the end user with the requirement of the funders through establishing the role that each of the key stakeholders can take to promote success. We have tested this in Nepal with Practical Action in the Energy sector and hope to turn it into a useful tool for all working towards the completion of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Dr. Chloe Peach - Post Doctoral Researcher at New York University. (PhD gained from School of Life Sciences, University of Nottingham.) @ChloePeach_PhD

My field of research is surrounding molecular pharmacology and drug discovery. Pharmacology is the study of how molecules work in the body - from the molecules our bodies make themselves, to the medicinal drugs that doctors prescribe to us. Unfortunately, many diseases still have ineffective medicines. Pharmacology is therefore particularly interested in what new medicines could be designed to treat disease. The ideal pharmaceutical drug would be effective and safe, but unfortunately many still have side effects. For example, painkillers that are able to reduce our pain can also lead to some horrible symptoms (e.g. opioids).

A fundamental way of making drugs work better is by understanding how the body differs at a molecular level between its healthy state and during disease. During both health and disease, different molecules can enter our cells by a process called endocytosis. This can be responsible for drugs coming into your cells from your bloodstream, or entry of the virus that causes COVID-19. This mechanism can also be exploited to make drugs reach the most effective region of a cell, such that they themselves undergo endocytosis to interact with their target proteins. My research is focused on how drugs can be delivered into cells themselves for more effective pain relief.

In order to look at how these molecules move around cells, we use state-of-the-art technologies to follow endocytosis in real-time. Specific molecules can be labelled using light, or fluorescence, such that they essentially glow in different colours. This allows us to visualise where the molecules are – such as a pain-causing protein or a pain-curing drug - in order to see whether the drugs are getting where they need to go. My research is investigating the dynamics of where molecules go to in cells, such that drugs can effectively reach these target sites.

Dr Cindy Vallieres – Research Fellow at the School of Life Sciences, University of Nottingham @Cindy_Vallieres

Fungi play a role in diverse, often contradicting, elements of human society. The first antibiotic, penicillin, was extracted from fungal cultures yet fungi are also a leading cause of human mortality. Recent estimates suggest that invasive human fungal infections kill more than 1.5 million people annually, more than major diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis. Similarly, fungi are widely used in the food industry (e.g., bread, alcohol, cheese) yet they can devastate food crops. 600 million people could be fed each year by halting the spread of fungal diseases in the five most important crops.

This is why producing chemical agents that work against harmful fungi is a large industry that is worth $30bn globally. However, the resistance of fungi to these agents is growing, underscoring the urgent need for new control strategies. As a research fellow at the University of Nottingham, my role is to develop new ways to control harmful fungi. With my colleagues, we have discovered two agents, that combined affect the process of protein synthesis in fungi, and have the potential to effectively abrogate fungal growth. This advance means also that lower amounts of these chemicals are needed which is cheaper and better for the environment.

But there are tightening regulations around the usage of such bioactive chemical agents. Consequently, potential bioactive-free technologies for fighting off fungi are highly attractive. We have therefore developed recently an alternative solution to tackle fungi, which does not actually kill the fungi. Instead, we can use polymers made out of (meth)acrylate which are coated onto medical devices or plant leaves. They stop the fungi from attaching to the surfaces and this means that a fungal infection is prevented “passively” by the coating.

Getting to know Raphael Achache

@raphaelachache ([email protected])

Are there specific materials, contexts in which you make your work?

I really enjoy working with all manner of materials. Watercolour, Acrylic, Inks, each with their own qualities and characteristics. Although most of my Commercial work happens digitally; the time saving and portability are just too great an advantage not to. That said, there’s nothing like getting the paints out and making a big old mess.

Where do you find inspiration?

I used to really struggle with this. then I realised it’s not the lack of inspiration that blocked me from creating rather the fear of the creation not looking decent enough. in reality, if you start something and you don’t like it… Just throw it away and do something else. Generally, if you give it everything you’ll either have something to be proud of. or, worst case, you’ve only wasted a sheet of paper and learnt a lesson.

How did you start making art?

Since I could hold a crayon really. I was about 22 (2011) when I realised I could make a living off it.

Can you think of a specific story or event over the years that boosted your creativity?

Travel is a huge source of inspiration for me, people, places, landscapes. Over the last two years, I have worked as a live illustrator. This has taken me to a number of cities all over the world. I’d always take my camera and on my days off Id walk around taking in the sights. Just recently I’ve been digging through these photos and turning them into paintings.

Did you ever encounter any obstacles regarding your work, and how did you manage to overcome them?

I’m also a musician, sometimes finding the balance of how much time I dedicate to a discipline can be a challenge. Although if I did one without the other I’d probably be bored or go a bit mad.

How did Covid-19 affect how you could work on this and other projects?

I think one of the most devastating effects of this virus for me is a little more subtle. Aside from the obvious, there has been the lack of incidental opportunities. All creative industries rely heavily on reputation and word of mouth. You bump into someone in the street on their way to a meeting, they discus a project that requires an illustration and suddenly you’re at the front of their mind. I never realised how effective this type of networking was until it was gone. The only alternative now is to do this all virtually on Instagram and linkedin, but I find that world all so boring and artificial.

Were you interested in science before participating in Creative Reactions?

I’d say not hugely but maybe more so than you’re average person. I enjoy listening to podcasts that explore phenomena in nature, inventions and new discoveries. The infinite monkey cage, Stuff you should know, ridiculous history To name a few.

How would you describe the benefits of collaborations between art and science?

I’ve recently picked up a book first published in the early 1900’s called Constructive anatomy. In which the author [George Bridgman] introduces a method of drawing the human figure that requires a deep and thorough understanding of the human body, with all its bones, muscles, and ligaments. The point of this approach is to visualise forms with scientific accuracy in order to perfectly express a gesture or pose. I think this harmony between art and science has existed indefinitely; the two are inseparable really.

About this post

This blog post is part of the Creative Reactions Nottingham 2020 online exhibition. Over the month of September, we will be bringing you different examples of collaborations between art and science, including a chance to get creative yourself. More Creative Reactions Nottingham blog posts.