© Pint of Science, 2025. All rights reserved.

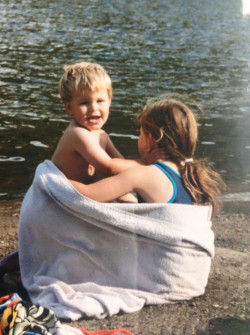

For many of us, visiting the beach is a fond childhood memory, with around 270 million people visiting the UK’s coastline each year. I have many happy memories of eating sand-filled sandwiches and poking about in rock pools with my brother. Now as an adult, the sea still fills me with wonder; its vastness helps me put life into perspective. But is it more than nostalgia that draws us towards the seaside?

It wasn’t until joining the BlueHealth Project that I stopped to consider the scientific evidence that backs up these thoughts and feelings. I’ve been helping the team analyse the BlueHealth Survey. This huge set of online data is the biggest of its kind, representing 18,000 individuals from 14 European countries plus Australia, California, Canada and Hong Kong. The data is helping us understand why, how and where people visit blue spaces like the coast. This is exciting because we can look across countries and continents to discover whether the benefits to health and wellbeing are consistent.

What exactly do we mean when we talk about ‘blue space’?

You might be more familiar with the term ‘green space’; things like grassland, trees and flowers, with a few birds and butterflies chucked in for good measure. Nearly 40 years of research has shown that spending time in green space is good for our mental and physical health and wellbeing.

Blue space refers to areas of water; ranging from the sea, to rivers, lakes, ponds, and even fountains. But less is known about the effects that blue space has on our health and wellbeing, especially in urban environments.

What can blue space tell us about our health and wellbeing?

Although spending time in nature has been found to be good for your health and wellbeing, inequalities can impact how easily and how likely people are to visit outdoor spaces. In England, it is reported that approximately one in six adults are affected by mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression, and these are far more likely in people from poorer backgrounds. This is where the sea comes into its own.

Research by Dr Ben Wheeler, at the University of Exeter, revealed that people living near the coast tend to have better health than those living inland. This finding was supported in a recent study by Dr Jo Garrett, also at the University of Exeter, who similarly found these benefits were especially true for people living in poorer households. She found that poor urban households living less than one kilometre from the UK’s coastline are around 40% less likely to have mental health symptoms compared to poor communities who live 50 km away. This suggests that the coast has a positive effect on people’s health and wellbeing and could play a role in reducing income-related health inequalities.

How research can help more people access blue spaces

With everyone in England living within 70 miles of the coast, and almost one in twenty living in one of England’s 37 principal seaside towns, understanding urban blue spaces is more important than ever. While Natural England has been improving access to the whole of the England’s coastline, not all blue environments are as easy to access. Research can help inform planners and policy makers about ways to improve how blue spaces are built and managed, so more people can access nature in towns and cities.

A good example of this is the regenerated inner-city beach in Teats Hill, Plymouth. Before, the space was a ‘forgotten corner’ of the city. But now it provides seating and a small outdoor theatre that’s used for community events. The BlueHealth project is doing similar interventions across Europe, to find out how improving access to blue spaces increases visits and improves health and wellbeing.

Similarly, this can be applied to everyday life. Imagine your commute consists of a 30-minute walk. Research shows that spending 120 minutes in nature each week is enough to boost your health and wellbeing. So your commuter journey on foot 4 times a week could be enough to boost your health if you pass through blue or green space. If town planners know about this, it can help them make decisions to regenerate disused fountains or improve canal-side pavements for example. This could transform your commute from something which was previously grey and dull, into part of a healthier daily routine.

So the next time you take a trip to the coast, walk past a fountain or stroll along a canal, take a moment to stop and reflect. Think about what these blue spaces mean to you, and how they make you feel. For me, they’re still all about the rock pools, although now I avoid sandy sandwiches.

About the author: Dr Bethany Roberts is a researcher on the BlueHealth project looking into how we can assess the potential benefits of visiting blue spaces across spatial scales. She is passionate about understanding people’s connections to nature, and how this can positively impact mental health and wellbeing.

About BlueHealth: The BlueHealth Project is a pan-European project which brings together researchers and experts to investigate links between public health and urban blue spaces. To find out more about the different research investigations underway visit: https://bluehealth2020.eu/. The BlueHealth Project is funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 666773.