© Pint of Science, 2025. All rights reserved.

Colourful Ideas. Acrylic Pouring by Lynda Jackson

The artist Lynda Jackson collaborated with the scientist Philip Moriarty for the 2019 Creative Reactions exhibition in Nottingham. She used a technique called Acrylic Pouring to explore the concept of Philip’s research on nano-cells. She says:

“When I met with Philip, we discussed his numerous strands of research and I had a pre-formed idea as to how I might represent his work on sound waves. It was when I mentioned a technique that I’ve wanted to experiment with called Acrylic Pouring and showed Philip some examples that the decision was made to use this technique, hopefully assisting with his research on nano-cells.”

Nanoparticles. Acrylic Pouring by Lynda Jackson

Lynda then approached her artwork like an experiment, similar to how a scientist explores the unknown:

“Acrylic Pouring typically uses a mixture of paint, a “pouring medium” and a drop or two of silicone oil, with the result sometimes being subjected to heat. Having tried different experimental mixes and techniques it soon became clear that it was impossible to repeat the same result even using consistent mixes. My experimental objective was to create cells in the artwork. Having not tried this type of art before it has been a revelation as all of my previous artwork has been very precise.”

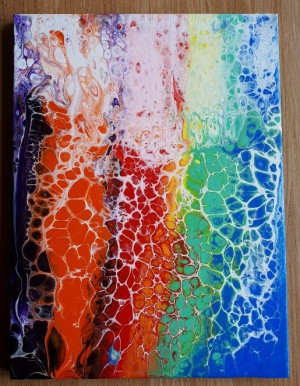

Rainbow Cell. Acrylic Pouring by Lynda Jackson

Acrylic pouring as a technique is an example of science and art working together in new and unexpected ways.

“Although only recently receiving attention, the technique has been known since the 1930s, when a Mexican artist, David Alfaro Siqueiros, almost by accident, discovered the effect and explored the aesthetics that resulted from a coming together of science and art which resulted in complex and beautiful creations, achieved almost without human intervention.

It seems that Siqueiros was marvelling at the science of Fluid Dynamics, wherein the different pigments in paints result in different densities and as the more dense paint tries to move downward, the paints may mix but often create the appearance of cells on the canvas.”

Getting to know Lynda Jackson

We asked Lynda about her artwork and the collaboration with Philip:

Are there specific materials, contexts in which you make your work?

Not normally as I usually paint with watercolours or acrylic paints but in carrying out this experiment of acrylic pouring I used silicone oil in my paints that caused a separating effect that resulted in patterns and formations which created its own unique artwork.

Where do you find inspiration?

Normally everywhere in life, what I see, what I feel, read and imagine but with this technique it is its own inspiration and I just tweak it.

How did you start making art?

My art is very different to the sort I produced for the Creative Reactions and it started when I retired and had time to spend on a hobby for myself. I started as a complete novice and produced quite good replica of my photographs

Can you think of a specific story or event over the years that boosted your creativity?

I belonged to a local Art Society and entered their annual competition which was judged by a local councillor. I won the competition for 6 out of 7 years.

Did you ever encounter any obstacles regarding your work, and how did you manage to overcome them?

My main obstacle is that I find it difficult to advertise and sell my work – I have not overcome this yet.

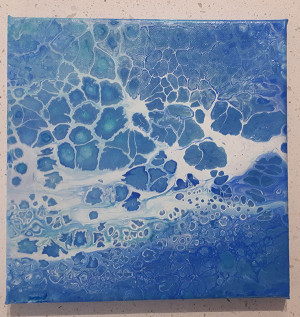

Sea Foam. Acrylic Pouring by Lynda Jackson

Can you describe the collaboration with your scientist – did you meet, email, speak online? What did you talk about?

I only met Philip Moriarty on one occasion where, after discussing the technique, we decided what I should do. After that I carried out experiments with the ratios of paint to silicone and sent him results in pictorial form and we corresponded over email.

Was there anything that surprised you during your collaboration?

Although I had no knowledge of physics and particularly nano particles (and still do not) I am amazed how often I see the patterns of these in natures structures etc.

How did Covid-19 affect how you could work on this and other projects?

In March I met my scientist (Sophie Evison of Nottm. University) for Creative Reactions 2020 and decided what I was going to do but Covid 19 altered this as it was cancelled and so I didn’t complete my artwork.

Were you interested in science before participating in Creative Reactions?

Only in a general day to day way but I do belong to a U3A Science Group.

Anything else that you would like to add?

I have really enjoyed the experience of collaborating with the Creative Reactions and Pint of Science programme.

Find more of Lynda's artwork on her website

For the Creative Reactions 2019 event, Lynda and Philip were interviewed by Richard Minkley and talked about their collaboration and about how art and science come together in unexpected ways.

Getting to know Philip Moriarty

About his role as a physics academic

Being an academic means combining at least three key roles: teaching, research, and admin/management. The latter I could do without but I love both teaching and research. I’d also add public engagement to the list – we academics are generally funded by the taxpayer so, as I (and many of my colleagues) see it, we have an obligation to explain what we’re doing with the money in as engaging a manner as we can. This is one reason I got involved with Brady Haran’s YouTube projects – Sixty Symbols, Numberphile, Computerphile, PeriodicVideos etc…

It’s rare that I do hands-on research these days. PhD students and postdoctoral researchers carry out the majority of the research. This is a real shame but it’s how academia has evolved. Some of the research within the group at the moment is focused on attempting to develop strategies to build structures by picking-and-placing single atoms, a type of 3D printing with atoms. If that’s even partially successful within the next decade or so, I’ll be over the moon!

About what he enjoys (most) about being an academic

On the teaching side, it’s when a student’s confusion gives way to an understanding of a conceptually challenging topic. As teachers, we’re too often reluctant to admit that confusion has played a large role in our learning – we forget that a major part of developing understanding is when we feel stupid; really stupid. On the research side, it’s that moment at 4am when you see something in the lab that no one in the world (or perhaps no one in the universe) has ever seen before…

About how he decided to become an academic

I wanted to become an academic from about the first year into my PhD. I wasn’t a great undergraduate student – I was too focused on music where can I order valium online and, um, related activities. Failing my exams in the third year of my four year degree course was the best thing that happened to me. [Philip Moriarty failed his third year of a physics undergraduate degree because of heavy metal music. He started playing guitar in a metal band during his university years in Dublin, Ireland. The hobby began to affect his school work until his academic failure gave him the “kick in the arse,” as he puts it, to really apply himself.]

Without failing those exams, I’d have drifted through my fourth year and graduated with much lower marks. My PhD supervisor was great and he made a huge difference in my decision to go for a career in academia – he provided just the right level of independence and direction throughout my PhD.

About how the connection between music and physics inspires him

There are lots and lots of links between physics and metal music, not only because a lot of physicists are big fans of metal. A lot of it has to do with the concerts themselves. Take the mosh pit, for example: a huge group of metalheads, swinging their long hair up and down, bouncing around and crashing into each other with wild abandon. To the outsider, the movement seems random, often dangerously so.

It turns out that a mosh pit makes a pretty good analogy for the movement of the molecules that make up an ideal gas, which is a hypothetical gas used in physics where all the molecules are moving around. Heavy metal fans behave just like atoms! Despite the fact that to you it feels random, there’s actually quite a lot of predictability to what’s going on.

Or you’ve heard of the sine function — probably in high school math, in the context of trigonometry. But what you might not have learned is that the sine function is basically the simplest kind of wave. It’s an expression of something that oscillates back and forth, between two extremes, like a swing on a playground, a seesaw or a yo-yo. Our world is full of these waves, and so is music, because sound is made up of waves, or sine functions.

Notes are actually made up of a whole bunch of sine waves all tangled together, vibrating at various frequencies. The [electric] guitar happens to have more, giving it that complicated sound — the “crunch”. Want a purer sound wave? You can get pretty close by whistling.

About the challenges of being a physics academic

I’d have to say that the greatest challenge is also the most enjoyable part of the job: the diversity of the tasks and roles. Balancing research, teaching, public engagement and admin, and being at least passable in each, is always a major challenge.

Crashing Waves. Acrylic Pouring by Lynda Jackson

About his collaboration with Lynda for Creative Reactions

I’ve been fascinated by the physics (and metaphysics) of foam for a very long time, and was delighted that the collaboration with Lynda serendipitously ended up being focused on foam-like painting and patterns. When we met for the first time, Lynda told me that she had a burgeoning interest in what’s known as acrylic pouring.

Foam patterns — or, to give them their slightly more technical name, cellular networks —are prevalent right across nature, from the sub-microscopic to the (quite literally) astronomically large. Our research group spent a great deal of time analysing the cellular networks that form when a droplet of a suspension of nanoparticles in a solvent is placed on a surface and subsequently left to its own devices (or alternatively spin-dried).

About seeing similar patterns in Lynda’s artwork and in the research on nano-scale

Physicists get very excited when they see the same class of pattern cropping up in very different systems and/or on very different length scales — it often means that there’s an overarching mathematical framework; a very similar form of differential equation, for example, may well be underpinning the observations. And, indeed, there are similar physical processes at play in both the acrylic pouring and the nanoparticle systems: mixed phases separate under the influence of solvent flow.

These answers were taken with Philip Moriarty’s permission from his interview with My Early Hour and interview with The Star and from his blog post about the collaboration.

Find out more on Philip Moriarty's blog and his videos on Youtube.

Not so Blue. Acrylic Pouring by Lynda Jackson

About this post

This blog post is part of the Creative Reactions Nottingham 2020 online exhibition. Over the month of September, we will be bringing you different examples of collaborations between art and science, including a chance to get creative yourself. More Creative Reactions Nottingham blog posts.